Ever since websites started being made essentially from JavaScript, transpiling this code to run in the largest number of different browsers has been an essential step in the build process. From the very beginning, more than ten years ago, the BedrockStreaming web application has relied on Babel for this task. This year we migrated from Babel to its next-gen replacement, SWC. It was not a smooth ride all the way, so let’s see what challenges we’ve had to overcome and if the payoff was worth the effort!

⚙️ Transpilation !? What’s that about ?

Generally, transpilation is the process by which you take some source code, transform it, and output a transformed version of source code (opposed to compilation where you output lower-level code than your source code).

In the JavaScript/web context, this means taking your code and transforming it into another version of the same language. But what is the point of transforming code into code?

The modern JavaScript code we write often uses features that aren’t supported in all environments. For example, older browsers that we want to support don’t implement every new syntax we are using. Another use case is server-side code, on the Node.js side we sometimes end up using modules or JSX in files that the runtime still expects in CommonJS. All-in-all, the transpilation transforms our newest syntax into older/more standard syntax that is supported in more environments.

Most transpilers use a plugin-based architecture: the core library is responsible only for parsing source code into an AST (Abstract Syntax Tree), performing the most common transformations (down-leveling the code to be compatible with older browsers for instance) and generating output code. All additional (more specific) transformations are handled by individual plugins, which are installed manually and added to the configuration. This separation of concerns allows easy customization and lets the community contribute new plugins without touching the core code. In other words, in modern transpilers, most custom code transformations are done via plugins.

Over the years, as the web technologies evolved, countless transformations have been added to the transpilation step. At BedrockStreaming, the transpiler handles all modern syntax, converting ESM to CJS modules, transforming TypeScript into JavaScript, transforming JSX into JS, etc., making it a cornerstone of our build process.

So the question isn’t whether we transpile or not, but how.

📦 The starting point: Babel

Babel is the first JavaScript transpiler, created to enable developers to write modern JavaScript code that could run in older browsers. Our project, now over 10 years old, has relied on Babel from the start, a solid choice built on robustness and flexibility. Being a 10-year-old tool is both a curse and a blessing! Because of its huge community, Babel can do almost anything: for nearly every need, there is a well-maintained and documented plugin available, and when you need to go off the beaten path, its API allows very specific and custom transformations. For a long time, this foundation was a real advantage, reliable, extensible, and almost indispensable for handling the transpilation of a complex project.

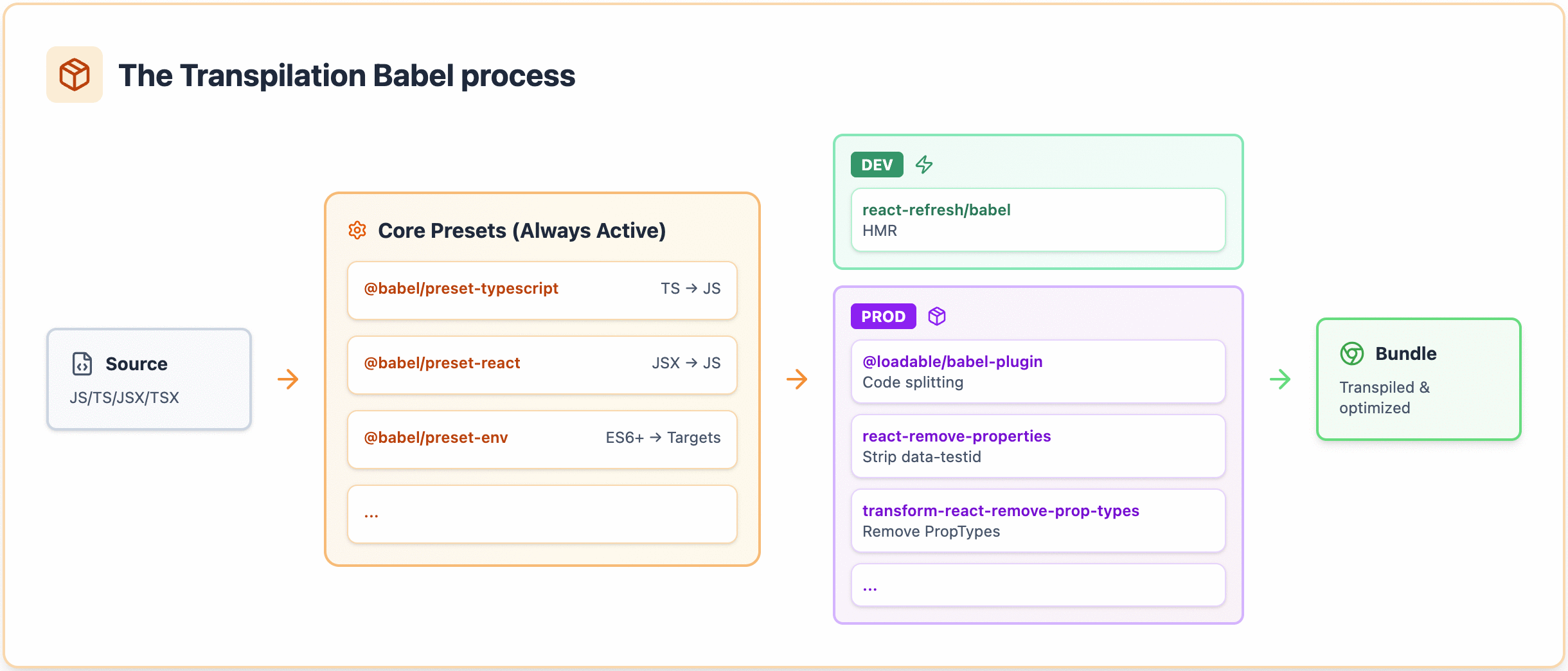

In Babel, all transformations happen through presets and plugins.

ℹ️ Plugins are pieces of code which perform a single transformation on a piece of code. A typical Babel pipeline consists of several plugins which sequentially transform the input source code.

ℹ️ Presets are plugins that are grouped together for convenience in order to fill a more general use case. For example,

@babel/preset-envcompiles modern JavaScript for the targeted browsers,@babel/preset-reacthandles JSX, and@babel/preset-typescripttranspiles TypeScript. Each of those presets actually return a group of individual plugins, which are then applied sequentially to transform the code.

The architecture of Babel allows us to enable different sets of plugins depending on the environment to achieve optimal bundle size/build time/developer experience. For instance, on top of all the traditional transformations (TypeScript, JSX, preset-env…), here are some plugins we enable only conditionally:

In development:

react-refresh/babelto enable Hot Module Replacement and improve the Developer eXperience (DX)

In production:

- Code splitting via

@loadable/babel-plugin - Removal of attributes like

data-testidwithreact-remove-properties - Removal of PropTypes with

transform-react-remove-prop-types

On the flip side, when we started looking more closely at our bundler, Webpack, compilation times, the limits of Babel became obvious. A quick analysis showed that babel-loader alone accounted for roughly 50% of the total build time (around 35 seconds out of a 1-minute build). In other words, even if everything else were optimized, transpilation would still remain our main bottleneck.

ℹ️ In a Webpack-based setup, most of the transpilation work happens inside loaders. Webpack itself is responsible for building the dependency graph, but every file then goes through one or more loaders to be transformed before being bundled.

In our case, babel-loader sits on the hot path of the build: every JavaScript file passes through it (at the time of writing this article, we have almost 5,000 JavaScript/TypeScript files in our project). This makes it one of the most impactful pieces of the pipeline in terms of performance. Optimizing this step, or replacing it with a faster alternative, is where the biggest gains can be achieved.

The long build time has a lot of implications: it is more costly in CI time, but above all, it translates to longer start times for our local development servers, which was starting to become a huge pain point as the application grew more and more with start times upwards of a minute. Since builds happen constantly—every time a developer starts their local environment, on every CI pipeline run, and during deployments—even small improvements compound into significant time savings across the entire team and infrastructure.

We were faced with a trade-off: continue benefiting from Babel’s massive ecosystem, or look for something significantly faster to improve compilation speed. Since our goal was clear: a better DX and higher performance, the question naturally arose.

This is where SWC (Speedy Web Compiler) comes in. SWC is an extensible, Rust-based platform for the next generation of fast developer tools, already widely adopted by modern frameworks and companies. It is positioned as a much faster alternative to Babel, with a simple promise: “SWC is 20x faster than Babel on a single thread and 70x faster on four cores.” More than enough to seriously question our existing stack and justify exploring a migration to a compiler designed from the ground up for performance.

⚠️ The PropTypes issue: missing remove-prop-types support

One limitation we quickly ran into was the lack of support for removing PropTypes in SWC. This became a problem because PropTypes, while largely deprecated in modern React applications, were still present in parts of our legacy codebase. Without stripping them, our production bundles remained unnecessarily large, and build times were impacted.

ℹ️

prop-typesis a legacy React library created to help type the props of React components. It has been deprecated since 2017 in favor of using TypeScript. The library allows you to declare the propTypes for a component in this way:MyComponent.propTypes = { propA: PropTypes.string, propB: PropTypes.number.isRequired, }It is this kind of code (only useful during development) that we want to remove from our production code.

SWC’s core is written in Rust and compiled into a native binary executed by Node.js. Plugins are also written in Rust, but they are compiled to WebAssembly (WASM), producing a single portable file that can run anywhere in a sandboxed environment. This architecture makes SWC extremely fast and portable, but it also means that features available in older transpilers (like Babel) may not exist yet.

Our specific issue is that there is no WASM plugin in SWC to strip PropTypes. PropTypes were effectively deprecated in 2017, so SWC being a modern transpiler doesn’t include this functionality out of the box. We found ourselves in a very specific case: trying to transpile a legacy app with cutting-edge tooling. It looks like we were not the only ones with this issue, the author of the Babel plugin to strip PropTypes opened an issue in 2021 exactly for this: SWC support.

At this point, we were faced with a frustrating dilemma: either renouncing and waiting for our codebase to be ready for the SWC migration, or trying to circumvent the issue to deliver the DX improvement as soon as possible. Here are the solutions we tried out.

💡 The solutions we evaluated

🗑️ Option 1 - Removing all PropTypes from the codebase

We initially considered simply dropping the library and removing all PropTypes in one shot. While this sounds somewhat ambitious for a large project, the PR would have been straightforward to review. Since we had started migrating parts of the codebase to TypeScript, we were on our way to removing the library anyway, albeit at our own pace.

This approach offers the “simplest” migration path from a technical standpoint and requires only a one-time effort with no ongoing maintenance afterward. It also results in a cleaner codebase because removing the library is our end goal anyway.

However, while this would require moderate effort, dropping PropTypes without adding TypeScript typing is risky, as it degrades the developer experience and could introduce bugs. There is also a potential regression risk during the removal process, and the change creates a large pull request surface area, which increases the review burden for the team.

❌ Why we didn’t choose this

After reflection and team discussions, we abandoned this approach given the extensive codebase. Even though the changes would have been theoretically simple to review, the sheer size of the PR could have potentially introduced unexpected regressions that would be difficult to trace.

🔌 Option 2 - Understanding ModernJS: WASM plugins vs JS re-implementations

Because there are no official prop-types plugins for SWC we looked for community plugins. We found one in swc-plugins, a plugins library for Modern.js, an open-source web framework created by ByteDance.

This library has a system of extensions, which are plugins ported from Babel, and one of these extensions is reactUtils. It features a removePropTypes option, so it looks like exactly what we were looking for!

We looked for a way to implement the plugin into our new SWC stack but we had a hard time simply plugging the plugin. This is because swc-plugins is actually a re-implementation of SWC: it’s a JS wrapper over SWC-core with a fixed set of available plugins. We were not the only ones to simply want the SWC plugin without the whole re-implementation, an issue was actually opened in swc-plugins since a year without any response.

We still tried to implement the standalone transpiler like in the docs, but quickly it was obvious that this would be an alternative to vanilla SWC and not a plugin. We were actually adding a whole new transpiler to our application!

We tried to make it work this way, but we soon found another issue: we couldn’t use official SWC plugins with this new compiler. This was a major blocker for us because we already need some official plugins that are not available in the swc-plugins compiler, like plugin-react-remove-properties to strip data-testid attributes from our production builds. Moreover, it didn’t give us a lot of trust towards this stack and its future evolution: we were basically locking ourselves out of all the official and community plugins to use a compiler from a repository with 64 stars and no activity since September ‘24.

To sum it up, we lost a bit of time trying to make this solution work because the swc-plugins repo is pretty well referenced and it looks exactly like a collection of plugins for any SWC users (even though it was made for Modern.js). It turns out that it is a very specific tool almost only used for Modern.js and it isn’t suited for people using a normal SWC stack.

🦀 Option 3 - Writing the missing plugin in Rust

Another solution we tried was to prototype a PropTypes removal plugin in Rust that would be compatible with SWC.

This was quite challenging since we’re not Rust developers 😅. We had to move fast and see how far we could get by creating a POC with Cursor. The first step was to analyze what babel-plugin-transform-remove-prop-types was doing. The entire logic was contained in a few source files, which we used to prompt the agent to translate into Rust.

After reading the SWC documentation on how to write a plugin, setting up the environment, and initializing a new plugin project with Cargo, we began iterating with Cursor. We achieved a POC that works very similarly to the Babel plugin in a short amount of time.

However, the challenges with this approach are the ongoing development investment and, more importantly, the time needed to build a clean and well-tested plugin. Since we’re not Rust developers, building and maintaining this codebase could become costly, even with agent assistance. We would also need feedback from the SWC Rust developers through the swc-project repository.

We plan to contribute this plugin to the community repository so it can be reviewed, merged and hopefully maintained by developers with real Rust expertise. We’re planning to move forward on this in the coming months.

In the meantime, we needed an alternative to avoid being blocked.

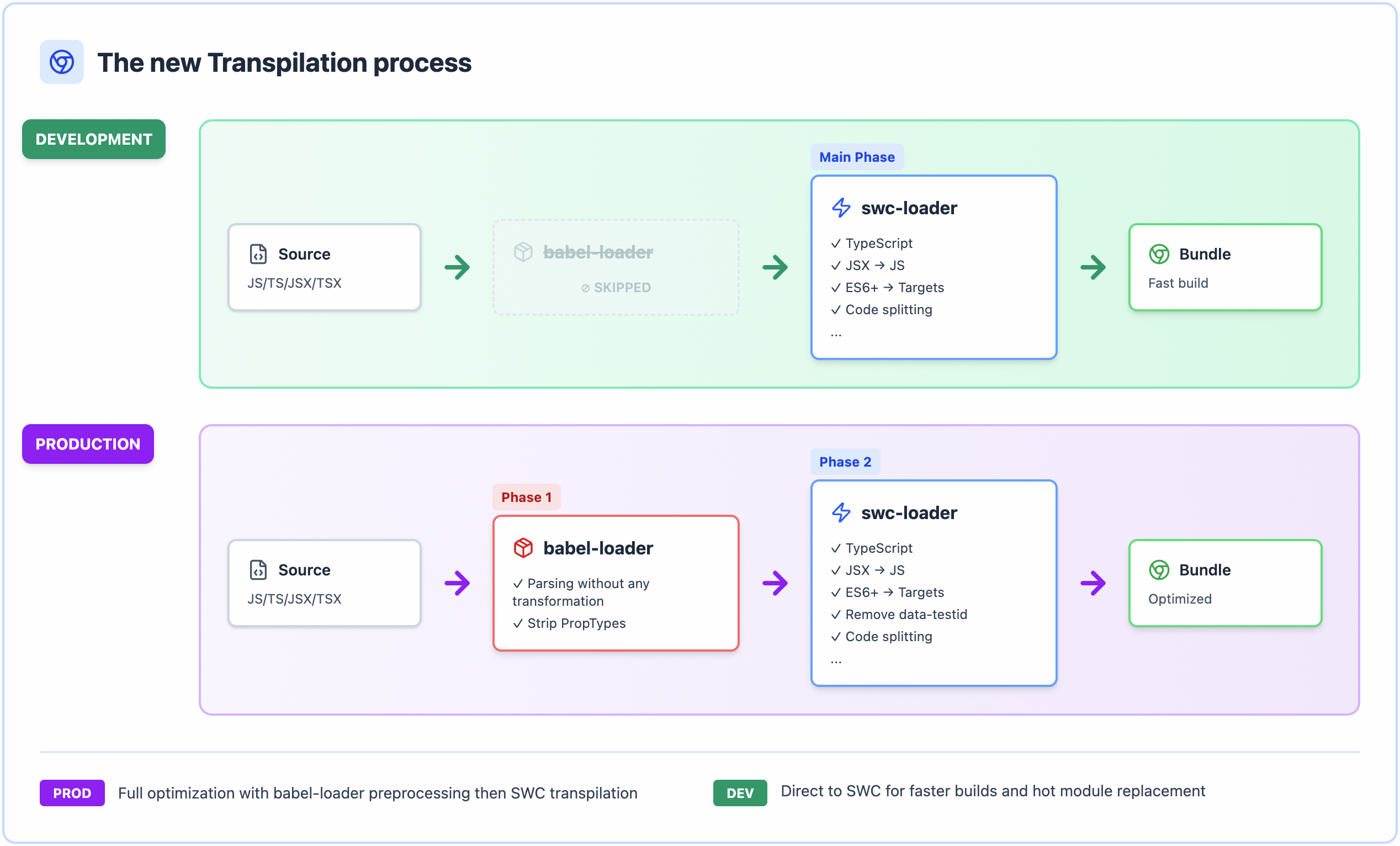

🤝 Option 4 (chosen) - Using a hybrid setup with Babel + SWC

In the end, we took a step back and reconsidered the problem: we had tried three alternative solutions to overcome the issue of removing propTypes from our production build. This proved very costly, if not outright impossible. We thus had to find a compromise: taken individually, removing propTypes is a minimal transformation compared to the 50+ other transformations we apply to our JavaScript files. What if we kept Babel only for this transformation and still migrated to SWC for all the other transformations?

The implementation of this double setup was actually made fairly easy by leveraging Webpack loaders. In our webpack configuration for JavaScript files, we specify two different loaders. Babel-loader goes first and only removes prop-types (very importantly, it doesn’t perform any other transformation and returns untransformed files except for prop-types removal). Then the SWC loader takes the output of babel-loader and performs all the transformations.

Babel-loader is only enabled for prod builds in order to keep the dev experience as smooth as possible.

This has a cost, of course, because there is the overhead of running all files through both Babel and SWC, but overall we expected an improvement in performance, only slightly less than what we could have achieved running only SWC.

What’s more, this hybrid setup is a temporary solution while we finish migrating away from prop-types, so we were looking for a solution that would allow us to bring the build time improvements as quick as possible, even if the setup isn’t definitive and will be tweaked in the future.

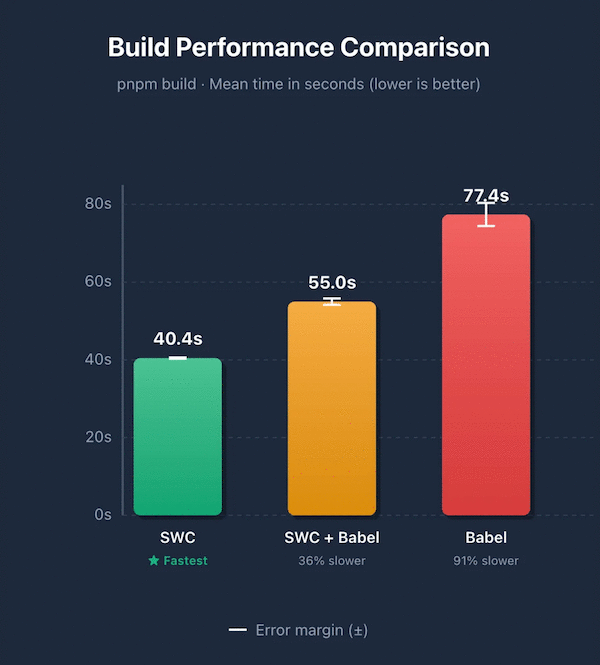

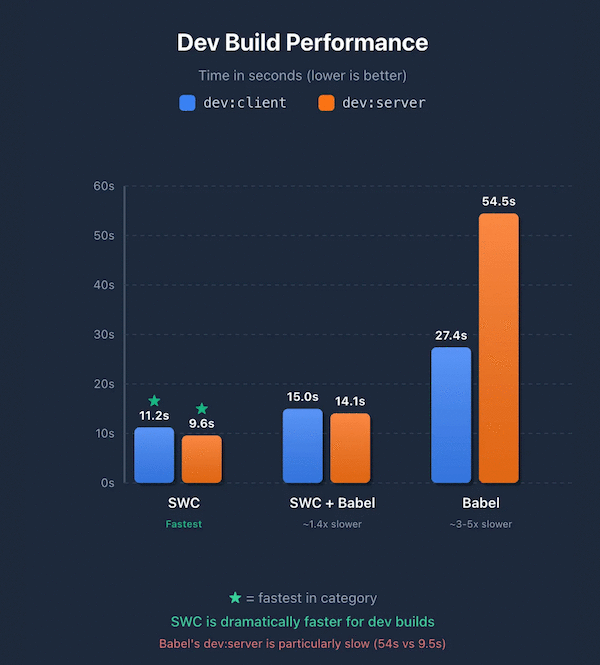

📊 Benchmark results

ℹ️ For the SWC part, we measure SWC here without removing PropTypes.

🏗️ Build times (without cache)

Production builds improved significantly: 77.4s (Babel) → 55s (hybrid SWC + Babel) → 40.4s (pure SWC). Development builds saw even more dramatic gains: dev server 54.5s → 14.1s and dev client 27.4s → 15s. Even with our hybrid approach, SWC delivers substantially faster builds.

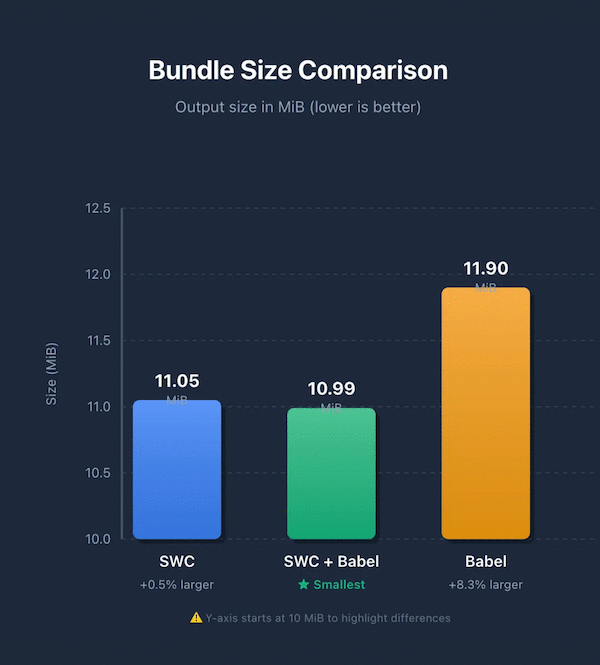

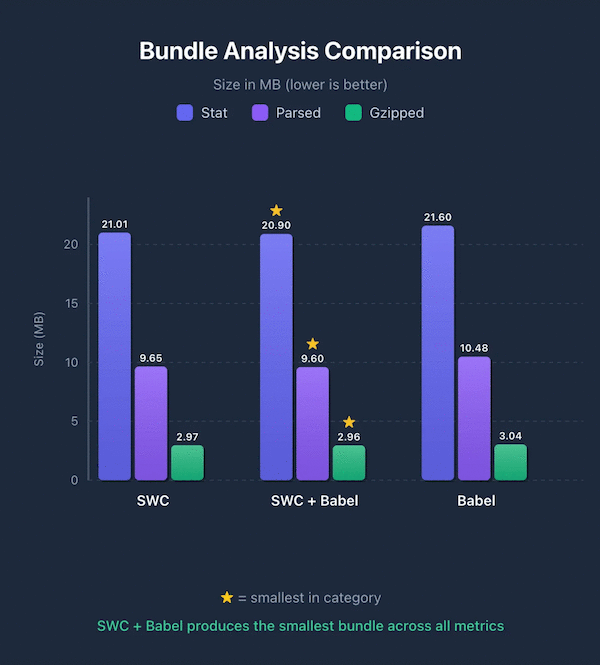

📦 Bundle sizes

When looking at the bundle size graph, the difference is actually quite small (1 MiB): using SWC without stripping PropTypes results in a bundle that is only slightly larger than our hybrid setup combining SWC and Babel. On paper, this might suggest that the additional complexity is not strictly necessary.

However, we deliberately chose to prioritize bundle size over development-time convenience. Production bundles are what ultimately get shipped to users, and keeping them as lean as possible is both a performance and a cleanliness concern. PropTypes are a development-time safety net; they provide no value in production and should not end up in the final bundle. Leaving them in, even with a marginal size impact, means knowingly shipping dead code.

From our perspective, this is less about chasing a few kilobytes and more about maintaining a clean production pipeline. Even if the gains are small today, enforcing this separation keeps the build process explicit, predictable, and aligned with how the code is meant to be used.

🚀 Next steps?

Looking ahead, there are a few clear steps to further improve our setup.

One of the first improvements we plan to adopt is @swc/jest. By replacing the default JavaScript-based Jest runner (like ts-jest) with this drop-in Rust replacement, our tests can run significantly faster. SWC’s Rust/WASM architecture makes it possible to apply the same transformations much more efficiently, which should reduce overall CI times and improve the feedback loop for developers.

On a longer-term horizon, we also plan to remove the remaining parts of the legacy PropTypes code. The migration has been designed in a way that makes it easy to phase out the remaining Babel setup once these PropTypes are gone. Even with this hybrid setup for now, the performance gains are already significant, and the codebase is noticeably more efficient.

It’s also worth mentioning that SWC’s documentation can be limited when it comes to more specific or advanced use cases. A big part of this migration involved experimentation, reading source code, and validating assumptions through benchmarks. We hope this article can help others facing similar constraints and reduce some of the friction we encountered along the way.

Throughout this process, our goal was clear: push developer experience as far as possible without compromising the quality of the final production bundle. And while this migration alone already delivers strong gains, it really starts to shine when combined with other optimizations, such as smarter caching strategies. More on that in a follow-up article.